Beresford Hall, Daniel Island, SC

Rick Mullin, Vice President and Charleston Area Manager for Simonini Builders, can hardly mask his enthusiasm once you get him warmed up talking about Beresford Hall, a new waterfront community just off Clements Ferry Road North on the Cainhoy Peninsula. “Beresford Creek is a major tributary of the Wando River, and it’s one of the prettiest and most pristine bodies  of water in the Charleston area,” he says. “To call it a creek is deceptive; it’s a significant body of water, and it offers deep-water access.” Looking from the community pier, stretching out over the broad expanse of marsh and the river beyond, it’s hard to argue with him. And it’s quiet. Country quiet. Remarkably, Beresford Hall is also only minutes away from I-526, downtown Charleston and Mount Pleasant, and one exit from the amenities of Daniel Island.

of water in the Charleston area,” he says. “To call it a creek is deceptive; it’s a significant body of water, and it offers deep-water access.” Looking from the community pier, stretching out over the broad expanse of marsh and the river beyond, it’s hard to argue with him. And it’s quiet. Country quiet. Remarkably, Beresford Hall is also only minutes away from I-526, downtown Charleston and Mount Pleasant, and one exit from the amenities of Daniel Island.

Still, it’s easy to forget the hustle of city life once inside the gates of the community. Words such as community and neighborhood are often heard when talking to anyone involved with Beresford Hall. It’s obvious that everything was planned with community in mind—not community in the simple sense that it contains houses, but community as a philosophical concept. Having built three houses there, Ernie Diloreti, owner of Diloreti Construction, summarizes, “It is just a well-planned, family-centered community.” Good luck finding someone involved who refers to Beresford Hall as a development.

Grange Cuthbert, who is with Prudential Carolina Real Estate, says that the developer, Greenwood Development, is rare because unlike so many developers, “they don’t try to cut costs just to make more money.” For example, he points out that John Morgan, project manager for Greenwood, identified 581 “grand trees” on the 600-acre property. From the very start,  John vowed to save every one of them, and he did—at no small expense. “It would have been a lot easier and less expensive to cut some of them, but he didn’t,” says Grange, who was so impressed with the master plan for the community that he decided to build a house there himself. “Having worked with Greenwood in the past, I knew that they would fulfill all their promises,” he adds.

John vowed to save every one of them, and he did—at no small expense. “It would have been a lot easier and less expensive to cut some of them, but he didn’t,” says Grange, who was so impressed with the master plan for the community that he decided to build a house there himself. “Having worked with Greenwood in the past, I knew that they would fulfill all their promises,” he adds.

Beresford Hall offers plenty of elbowroom. Lots are at least three quarters of an acre, while some go as high as three. “Most developers would have squeezed many more lots out of a property this size, but that was not Greenwood’s vision,” Grange points out. Lots range from deep-water sites with piers to interior lots overlooking ancient fields (one of which predates the colonial era) lined with ancient moss-draped live oaks. In addition to lot size, Ernie points out that required natural curtains and clearing guidelines for each lot enhance both privacy and the rural attitude of Beresford Hall, plus there are numerous permanent green spaces, such as an eight-acre meadow and five parks dotted throughout the community.

The fields and oaks are living artifacts of land that boasts a rich history. First hunted and farmed by American Indians, the land was deeded to Richard Beresford in 1706. Over the years, the site has witnessed brickworks that supplied the Charleston market (piles of these early manufactures rest where they were left near the community pier), the unsuccessful cultivation of silk and the genteel pursuit of Lowcountry game.

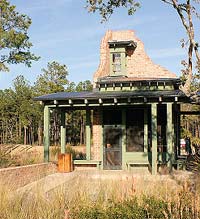

Today, the epicenter of Beresford Hall is the community center—“The Ruins”—cunningly designed to reflect a ruined 18th-century brick plantation house. Designed by preeminent architect Jim Thomas, the center features a large pool pavilion with a rustic lodgelike dining room and deep porches with an enormous covered grill and outside fireplace. The adjacent swimming pool overlooks the marsh. Rearward and to the side of the center, the icehouse—a smaller architectural “ruin”—shelters a commercial ice machine and sits beside the community boat launch, convenient for fishing, skiing or a sunset cocktail cruise.

From a builder’s perspective, both Rick and Ernie agree that one of the most attractive benefits of Beresford Hall is its relatively high ground. Some lots are as much as 20 feet above sea level. “I even have one that’s pushing 30 feet—an unusual feature in coastal South Carolina,” Rick says. He adds that having such high ground in a waterfront community is a marked advantage for builders because it invites so many more fl oor plan options. “In many cases, we are able to build out instead of up, providing grand living on a single level,” he explains.

Beresford Hall promises other activities in addition to water sports. Eight miles of walking trails and sidewalks accommodate biking and observing nature. For all its privacy, Beresford Hall’s parks and ponds, as well as a central post offi ce and the Grand Council Mall, reinforce the emphasis on family and community.

Young families in Beresford Hall will send their children to the soonto- be-opened Daniel Island Elementary School. Being part of this school reinforces Beresford Hall’s relationship with Daniel Island and all its amenities, but within a rural context.

Although there is no architectural master plan for the community, a strict building review board assures that all architectural plans relate to Beresford Hall’s Lowcountry character. “The review board here is tougher than in other places we’ve built,” Ernie claims, “and that adds to the value of the neighborhood.”

In keeping with such high standards of quality, Ernie pays special attention to details that make each house he builds in Beresford Hall unique. For example, he’s included cherry cabinets, made in Diloreti’s own workshops, in some kitchens. “Nobody will be able to walk into one of our kitchens and say, ‘Oh, I have that,’” he says.

An ardent student of Lowcountry architecture, Rick points out that although this vernacular style is simple, the details are meticulous. “The proportions of dormers, the alignment and entablature of columns and porches, the casings and head conditions of windows—attention to all these authentic details are not something an untrained observer can immediately identify, but those with a good eye recognize design when its done right,” Rick says. “Charleston is one of three major colonial centers with a rich architectural history,” he adds, “and I have an obligation to see that these traditions are executed faithfully in every house we build here.” Such a testimony should be no surprise coming from someone building houses in a community dedicated to the smallest details. As Grange puts it, “The clubhouse, post office, green spaces, parks, granite curbs—you rarely find such quality details in neighborhoods being built today.”