“We made it Evangeline. The worst is over.” These were the words that Thomas Williams spoke to his wife as he looked out the back door of his McClellanville home during the calm of Hugo’s eye. The view before him was pretty bad but it wasn’t devastating. For the most part, his house and the houses of his friends and relatives on DuPre street were in good shape.

“We made it Evangeline. The worst is over.” These were the words that Thomas Williams spoke to his wife as he looked out the back door of his McClellanville home during the calm of Hugo’s eye. The view before him was pretty bad but it wasn’t devastating. For the most part, his house and the houses of his friends and relatives on DuPre street were in good shape.

There was no way for Williams to know that in less than 30 minutes he, his wife and their four children, and indeed most of the residents of McClellanville, would be living the worst nightmare of their lives. The deadly wall of water that was hurtling toward this little picturesque fishing village was still fifteen miles away on the back side of the eye.

The first clue Williams had that things weren’t really over was the incessant whining and crying of his dog, Sonnie. “The dog is normally pretty quiet,” said Williams, “but that night he just wouldn’t shut up. My wife told me to let him inside because he was scared. Well I did, but he still wouldn’t stop whining. I was fixing to put him back out when the wind started howling again, this time with a vengeance.”

“I heard a cracking noise from the back of the house and saw part of the roof come off. I didn’t want the clothes in the back bedroom to get wet so I immediately started over there. As I walked down the hallway I could feel the carpet rising up around my feet. At first I thought that the wind was blowing so strongly it was lifting the carpet. Then I saw the water coming up through the floor and I knew we were in trouble.”

“I heard a cracking noise from the back of the house and saw part of the roof come off. I didn’t want the clothes in the back bedroom to get wet so I immediately started over there. As I walked down the hallway I could feel the carpet rising up around my feet. At first I thought that the wind was blowing so strongly it was lifting the carpet. Then I saw the water coming up through the floor and I knew we were in trouble.”

“I ran down to the kitchen, which is lower than the rest of the house , and saw that it was under about a foot of water. I thought our best chance was to get in the van and drive to safety so I told everyone to pack up whatever they could. I ran to the front of the house and started to open the front door — a glass storm door. That was a mistake because I could see at least three feet of water through the glass. I had to call my wife to help me shut the door.”

“I knew we were trapped inside the house so I told everyone to head for the kitchen because that was where the access door to the attic was. By then it was too late. The kitchen had about three feet of water in it and the appliances and counters were either toppled over or floating around. There was no way we could climb over all those things and get to the door. Besides, I couldn’t even find the ladder that was in the kitchen.”

“I rushed everyone into the kid’s bedroom because there was a huge dresser in that room we could all stand on. That was when I decided to bust a hole in the ceiling to get into the attic. The ceiling in that room was sheet rock over plaster and I had a devil of a time busting through. I pounded and pounded, and just as I put a hole in the ceiling, the water lifted that dresser up like it was a cork. We were all tossed into the water which was about three feet high at the time. We fished everyone out and they seemed to be okay but at that point I didn’t know what to do. We had nothing to stand on and the water was rising fast.”

“I rushed everyone into the kid’s bedroom because there was a huge dresser in that room we could all stand on. That was when I decided to bust a hole in the ceiling to get into the attic. The ceiling in that room was sheet rock over plaster and I had a devil of a time busting through. I pounded and pounded, and just as I put a hole in the ceiling, the water lifted that dresser up like it was a cork. We were all tossed into the water which was about three feet high at the time. We fished everyone out and they seemed to be okay but at that point I didn’t know what to do. We had nothing to stand on and the water was rising fast.”

“Just then my daughter said, ‘Daddy, look! There’s the ladder.’ Sure enough, like a gift from God, here came the ladder floating into the bedroom. I don’t know how it got out of the kitchen but it definitely saved our lives. I stood it up under the hole and began carrying the children up to the attic. It was pitch black in there and I told them to stay on the main beam and not to move. I knew if they stepped onto the sheet rock they would come right through the ceiling.”

“After my wife climbed into the attic I started throwing everything that was usable up there — clothes, food, flashlight, candles. The cooler floated by and I threw that up there, too. By then, the water was about five feet high so I grabbed the dog off the bunk bed and we climbed into the attic. All of this happened in a time span of no more than 10 to 15 minutes from when I first saw the water in the kitchen.”

“There were some panel boards in the attic and I laid them out so we wouldn’t have to sit on the rafters. Then I told my wife, ‘Listen honey, whatever you do, please don’t cry out or act frightened. It will only panic the kids.'”

“We were all up in the attic in the darkness, scared and cold, but at least we were alive – and for the moment, safe. I couldn’t think of anything else to do so we just prayed for a few minutes.

“When I looked down into the bedroom it was as if someone had turned a light on. I could see that room just as clear as daylight, even down to the pictures on the wall. I saw a bag of shrimp float out of the room and I remember saying to my wife, ‘There go the shrimp, trying to get back to the ocean.’ To this day I can’t understand where that light came from but it was a real comfort to be able to see something from the darkness of the attic.”

“We couldn’t find the flashlight but we managed to locate a candle. My wife had a fairly dry pack of matches in her coat pocket and she tried to strike one but it didn’t light. Thank god it didn’t because I suddenly realized there was a very strong smell of gas in the attic. We had a large propane tank outside, and one of the lines in the kitchen must have broken. I suppose that the water, which by this time was almost up to the top of the doorways, was pushing the gas into the attic. I knew we had to get out of there and into some fresh air so I made everyone crawl along the main beam toward the kitchen where part of the roof had blown off.”

“When we got there I looked out over the area behind my house and noticed my neighbor’s van with the lights on. I thought, ‘That poor fool must have tried to drive out when the water came and now they’re trapped in their van.’ I was going to tie a length of telephone cord we found in the attic around my waist and swim over there. My wife convinced me that the water was too rough and I’d never make it.”

As it turned out there was no one in the van. The salt water had shorted out the switches, and the lights came on by themselves. In fact, Williams’ neighbor, Wilbur Gibbs, was sitting in his attic thinking that Williams was the poor fool who was stuck in his own van.

For the next several hours, the Williams family, dog and all, sat huddled in the attic, completely unprotected from the hurricane force winds.

“The constant pounding and howling of the wind almost drove us crazy,” said Williams. “The rain pelted us like beebees and we had to dodge large objects that were flying by. I just kept saying, ‘Lord, won’t you please stop the wind.’

“I could see the waves of water outside and some of them were rolling over the backboard of our basketball pole. Then I heard screams from Lincoln High School. The school was about 300 yards from my house and the wind was roaring around us but we could still hear people screaming. I thought, ‘My God, if they can’t survive in there, how are we hoping to make it out here?’

“Some of the waves were reaching up to our roof and I was afraid that one of them might wash us out of the attic. Then I said to myself, ‘If that happens, which one of my children am I going to save and which ones will I let drown?’ So I grabbed the telephone cord and used it to tie us all together. I told them that it would keep anyone from floating away. In my own mind I decided that this way we would at least live together or die together.”

“About two hours after we had moved over to that part of the attic the water stopped rising and the smell of gas was gone. We crawled back over to the covered portion of the roof and laid down on the panel boards. The house was shuddering and shaking but at least it was still standing. Just then I felt a huge wave hit the house. That probably was the one that moved it although I didn’t know it at the time.”

“I guess I went to sleep for a few hours because the next thing I knew it was dawn. I could see my uncle’s house next door and it wasn’t in the same position that it was before the storm. I thought his house had moved.”

“Then everyone in the neighborhood started hollering from their attics, ‘Are you okay?’ and people would holler back, ‘Yes, we’re alright. How about you?’

“There was about three feet of water on the ground so I climbed down from the attic to check on my aunt and uncle who live near us. That’s when I realized my house had moved about 10 feet off its foundation. My uncle’s house was rock solid.”

“My uncle is partially paralyzed from a stroke and I was very worried about him. I found him lying in an upstairs bedroom, shaking and wet, but otherwise all right. I asked the woman who takes care of him, Betty Singleton, how she got him upstairs. She told me that she certainly couldn’t carry him upstairs so when the water started rising she floated him up the staircase.”

“Then I went over to my aunt’s house. She is an elderly woman with a number of physical problems. When I found her, her feet were so swollen she couldn’t walk, so i carried her over to my uncle’s house.”

“Then I walked over to Lincoln High fearing that I would find hundreds of dead bodies. Miraculously everyone survived. The principal kept asking the same question that everyone else was asking, ‘Why did they send us to this death trap?’

“Seeing everyone was okay I went back to my house to get my family down from the attic. My wife looked around at the wreckage in our house and she started crying, ‘It’s gone, Thomas. Everything we had is gone.’

“About 10 o’clock that morning a helicopter flew over and we all started waving and shouting at him. He dipped down as if to say he had seen us. At 4 o’clock in the afternoon a National Guard Truck arrived and picked up about 40 of us. They took us to the National Guard armory in Georgetown but that place was full so they drove us to Waccamaw High School on Pawleys Island. They told us that was where we were going to spend the night. That place had nothing: no food, no water, power, clothes or bedding. We had to lie on that hard cement floor all night. We were wet and cold, hungry and thirsty. It felt like we didn’t even exist.

“The next morning a truck picked us up and took us to Georgetown High School. The principal there did everything he could for us. He gave us dry clothes, even some of his own, and let us take showers in the gym. Then they took us to the First Baptist Church of Georgetown which was a Red Cross shelter. They had hot food, clothing and bedding. The minister of the church also helped with clothing and financial aid. He said that even if the Red Cross left, that would be our home until we found one.”

“We stayed there for about two weeks and then we moved into my sister’s trailer which now has nine people living in a place that is barely big enough for three. We were supposed to get a trailer from FEMA but they declared McClellanville a flood zone and won’t allow us to put a trailer on our property.”

And five weeks after Hugo hit Thomas Williams and his family still wait — for assistance from FEMA.

Hurricane Hugo brought a lot of hard work and inconveniences to all of us. We had to clear trees, patch roofs and live without power for a few weeks. For the Williams family, and for hundreds like them, Hugo has forever changed their lives. Their home is a twisted, gutted shell. It will have to be torn down and replaced with a new one. Since the Williams had no flood insurance, that won’t be easy.

They had just finished paying off a $15,000 home improvement loan and were looking forward to a bright future. There would have been enough money to send their kids to college and to do some traveling on their own. That will no longer be possible. Now they talk about the things they won’t have, not the things they will have.

At the time in their lives when they should be near the top of the mountain looking down they’re at the bottom looking up. For Thomas Williams and his family, the nightmare in McClellanville continues.

![]() The East Cooper area has grown from a suburb of Charleston into quite a metropolitan area in the last couple of decades. New neighborhoods have sprung up almost overnight, bringing wide new roads lined with shops and restaurants. There’s so much to do and see but when you tire of the everyday pursuits, here’s an idea. Take a little trip back in time. Visit some of the places that mean “Mount Pleasant and the Islands” to old timers and newcomers alike.

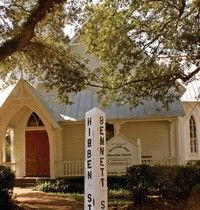

The East Cooper area has grown from a suburb of Charleston into quite a metropolitan area in the last couple of decades. New neighborhoods have sprung up almost overnight, bringing wide new roads lined with shops and restaurants. There’s so much to do and see but when you tire of the everyday pursuits, here’s an idea. Take a little trip back in time. Visit some of the places that mean “Mount Pleasant and the Islands” to old timers and newcomers alike.![]() If you’d really like to take a trip to a time gone by, don’t miss Mount Pleasant’s Old Village, where old historic homes jostle with their modern neighbors. This is the kind of neighborhood where people walk or bike to the original “business area.” Though only a block long, Pitt Street is still a thriving business center, featuring an upscale restaurant/bed and breakfast along with little shops and galleries. Don’t miss the Pitt Street Pharmacy, where you can stop in for a hot dog and soda—a genuine fountain soda, for those who can remember such a thing! Pitt Street Pharmacy, Old Village Alhambra Hall Much of the Old Village area is along the waterfront, although it can be hard to get more than a glimpse here and there as you drive along narrow tree-shaded streets. A spectacular view of the harbor and the Holy City itself awaits you at Alhambra Hall. You can walk around the grounds and enjoy the breeze. It’s a popular place for events such as the annual Blessing of the Fleet and is much in demand for weddings and receptions. Take a peek inside and you’ll see why—vaulted ceilings, hardwood floors and wide porches make this former ferry terminal a southern classic.

If you’d really like to take a trip to a time gone by, don’t miss Mount Pleasant’s Old Village, where old historic homes jostle with their modern neighbors. This is the kind of neighborhood where people walk or bike to the original “business area.” Though only a block long, Pitt Street is still a thriving business center, featuring an upscale restaurant/bed and breakfast along with little shops and galleries. Don’t miss the Pitt Street Pharmacy, where you can stop in for a hot dog and soda—a genuine fountain soda, for those who can remember such a thing! Pitt Street Pharmacy, Old Village Alhambra Hall Much of the Old Village area is along the waterfront, although it can be hard to get more than a glimpse here and there as you drive along narrow tree-shaded streets. A spectacular view of the harbor and the Holy City itself awaits you at Alhambra Hall. You can walk around the grounds and enjoy the breeze. It’s a popular place for events such as the annual Blessing of the Fleet and is much in demand for weddings and receptions. Take a peek inside and you’ll see why—vaulted ceilings, hardwood floors and wide porches make this former ferry terminal a southern classic. This area teems with all sorts of wildlife, from tiny fiddler crabs to majestic water birds. It’s a favored fishing place, as well. From the Pitt Street Bridge, you can almost see another East Cooper icon. It’s well worth the trip to Sullivan’s Island to pay a visit to Chief Osceola at Fort Moultrie (map link). The Seminole Indian chief is buried on the grounds, at the entrance to the fort. Named for Colonel William Moultrie, the fort was created with palmetto logs and sand, and it dates back to the Revolutionary War. The current structure was built in 1809 and served as home base to likes of General Sherman, of Civil War fame, and Edgar Allan Poe, who used Lowcountry settings in some of his work. There’s quite a lot history to be enjoyed here, and you’ll want to take it all in.

This area teems with all sorts of wildlife, from tiny fiddler crabs to majestic water birds. It’s a favored fishing place, as well. From the Pitt Street Bridge, you can almost see another East Cooper icon. It’s well worth the trip to Sullivan’s Island to pay a visit to Chief Osceola at Fort Moultrie (map link). The Seminole Indian chief is buried on the grounds, at the entrance to the fort. Named for Colonel William Moultrie, the fort was created with palmetto logs and sand, and it dates back to the Revolutionary War. The current structure was built in 1809 and served as home base to likes of General Sherman, of Civil War fame, and Edgar Allan Poe, who used Lowcountry settings in some of his work. There’s quite a lot history to be enjoyed here, and you’ll want to take it all in.

If ever Sullivan’s Island Police Sgt. David J. Price could erase a period of his life, he would most certainly eliminate the last two weeks of September and the first two weeks of October, 1989.

If ever Sullivan’s Island Police Sgt. David J. Price could erase a period of his life, he would most certainly eliminate the last two weeks of September and the first two weeks of October, 1989. The destructive powers of Hurricane Hugo, which struck the Charleston area on the night of September 21, were initially underrated by many locals, including Price.

The destructive powers of Hurricane Hugo, which struck the Charleston area on the night of September 21, were initially underrated by many locals, including Price. “We had a hurricane tracking map on the office wall, and we didn’t use it for show. We had been pinpointing it (Hugo), and followed it closely on the news. But on Wednesday (Sept. 20) we got the word from the Emergency Preparedness officials to evacuate the island.

“We had a hurricane tracking map on the office wall, and we didn’t use it for show. We had been pinpointing it (Hugo), and followed it closely on the news. But on Wednesday (Sept. 20) we got the word from the Emergency Preparedness officials to evacuate the island.

It was 8 a.m., Sept. 25, four days beyond Hugo. After an all night drive from Atlanta, my son’s evacuation home, I boarded the harbor-tour boat at Patriot’s Point for a return to the devastated Isle of Palms. In a pouring rain that added to the gloom, we were a rag-tag crowd gathered from all points of shelter.

It was 8 a.m., Sept. 25, four days beyond Hugo. After an all night drive from Atlanta, my son’s evacuation home, I boarded the harbor-tour boat at Patriot’s Point for a return to the devastated Isle of Palms. In a pouring rain that added to the gloom, we were a rag-tag crowd gathered from all points of shelter. This was the first boat to the island, and the first time anyone had been able to get back since the storm drove us away. To add another war-like dimension to the incredible scene, we, in effect, had to give our name, rank and serial number before boarding the boat. You had to have the proper ID to prove your right to take the “Isle of Palms Clipper.”

This was the first boat to the island, and the first time anyone had been able to get back since the storm drove us away. To add another war-like dimension to the incredible scene, we, in effect, had to give our name, rank and serial number before boarding the boat. You had to have the proper ID to prove your right to take the “Isle of Palms Clipper.” My thoughts were strange. Why did this Biblical phrase flash through my mind: “Many are called, but few are chosen?”

My thoughts were strange. Why did this Biblical phrase flash through my mind: “Many are called, but few are chosen?” “We made it Evangeline. The worst is over.” These were the words that Thomas Williams spoke to his wife as he looked out the back door of his McClellanville home during the calm of Hugo’s eye. The view before him was pretty bad but it wasn’t devastating. For the most part, his house and the houses of his friends and relatives on DuPre street were in good shape.

“We made it Evangeline. The worst is over.” These were the words that Thomas Williams spoke to his wife as he looked out the back door of his McClellanville home during the calm of Hugo’s eye. The view before him was pretty bad but it wasn’t devastating. For the most part, his house and the houses of his friends and relatives on DuPre street were in good shape. “I heard a cracking noise from the back of the house and saw part of the roof come off. I didn’t want the clothes in the back bedroom to get wet so I immediately started over there. As I walked down the hallway I could feel the carpet rising up around my feet. At first I thought that the wind was blowing so strongly it was lifting the carpet. Then I saw the water coming up through the floor and I knew we were in trouble.”

“I heard a cracking noise from the back of the house and saw part of the roof come off. I didn’t want the clothes in the back bedroom to get wet so I immediately started over there. As I walked down the hallway I could feel the carpet rising up around my feet. At first I thought that the wind was blowing so strongly it was lifting the carpet. Then I saw the water coming up through the floor and I knew we were in trouble.” “I rushed everyone into the kid’s bedroom because there was a huge dresser in that room we could all stand on. That was when I decided to bust a hole in the ceiling to get into the attic. The ceiling in that room was sheet rock over plaster and I had a devil of a time busting through. I pounded and pounded, and just as I put a hole in the ceiling, the water lifted that dresser up like it was a cork. We were all tossed into the water which was about three feet high at the time. We fished everyone out and they seemed to be okay but at that point I didn’t know what to do. We had nothing to stand on and the water was rising fast.”

“I rushed everyone into the kid’s bedroom because there was a huge dresser in that room we could all stand on. That was when I decided to bust a hole in the ceiling to get into the attic. The ceiling in that room was sheet rock over plaster and I had a devil of a time busting through. I pounded and pounded, and just as I put a hole in the ceiling, the water lifted that dresser up like it was a cork. We were all tossed into the water which was about three feet high at the time. We fished everyone out and they seemed to be okay but at that point I didn’t know what to do. We had nothing to stand on and the water was rising fast.” The point in time most vivid to one of them, Michael A. Pulliam, was acceptance of the belief that he would die. He and friend Kevin Williams were swept from a second floor of the house on the front beach and were propelled through twelve-foot white-water currents for a city block, landing finally on the roof of a one-story house. Sense of time was suspended, he says, the water, the wind and ink-black darkness were his only perceptions. “We didn’t scream,” he said. There wasn’t time.

The point in time most vivid to one of them, Michael A. Pulliam, was acceptance of the belief that he would die. He and friend Kevin Williams were swept from a second floor of the house on the front beach and were propelled through twelve-foot white-water currents for a city block, landing finally on the roof of a one-story house. Sense of time was suspended, he says, the water, the wind and ink-black darkness were his only perceptions. “We didn’t scream,” he said. There wasn’t time. “It was half crazy, I guess,” Pulliam said. “But I really like the outdoors in bad weather. We didn’t want it (Hugo) to hit, but we were excited about the onslaught.”

“It was half crazy, I guess,” Pulliam said. “But I really like the outdoors in bad weather. We didn’t want it (Hugo) to hit, but we were excited about the onslaught.” The two were in touch by phone with parents and friends in Columbia, who advised them of the progress of the storm. Pulliam’s mother called the Isle of Palms Police Department to report the presence of the two on the island,” Pulliam said. His grandfather called to instruct them to leave the house, a two-story brick construction, and go to the house next door, which is also two stories, but on stilts. “My grandfather was worried about the 12-18 ft. tidal surge predicted. He didn’t think the house would stand. There was nowhere for the water to go.”

The two were in touch by phone with parents and friends in Columbia, who advised them of the progress of the storm. Pulliam’s mother called the Isle of Palms Police Department to report the presence of the two on the island,” Pulliam said. His grandfather called to instruct them to leave the house, a two-story brick construction, and go to the house next door, which is also two stories, but on stilts. “My grandfather was worried about the 12-18 ft. tidal surge predicted. He didn’t think the house would stand. There was nowhere for the water to go.”

For the earliest settlers of Mount Pleasant, major routes of transportation included a multitude of harbors, channels, rivers, inlets and creeks surrounding the area. Many of the names that described these waterways originated with the Sewee and Wando Indians. For example: “Shemee” Creek, the “Wando” River and “Sewee” Bay. Other names of water passages spring from European origins such as the Ashley and Cooper rivers.

For the earliest settlers of Mount Pleasant, major routes of transportation included a multitude of harbors, channels, rivers, inlets and creeks surrounding the area. Many of the names that described these waterways originated with the Sewee and Wando Indians. For example: “Shemee” Creek, the “Wando” River and “Sewee” Bay. Other names of water passages spring from European origins such as the Ashley and Cooper rivers.

GREENWICH VILLAGE

GREENWICH VILLAGE

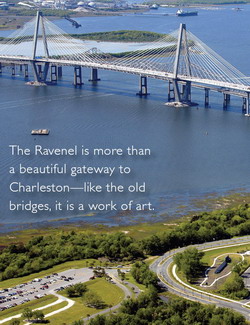

I resisted the temptation to drive the new Arthur Ravenel Jr. Bridge the first day it opened to traffic. Well, I did until dinner time. My daughter, Sam, and I had gone out for a salad at an eatery around the corner. On that two-minute drive home, I said, “Do you want to drive over the bridge?”

I resisted the temptation to drive the new Arthur Ravenel Jr. Bridge the first day it opened to traffic. Well, I did until dinner time. My daughter, Sam, and I had gone out for a salad at an eatery around the corner. On that two-minute drive home, I said, “Do you want to drive over the bridge?” To clutch the door handle was to potentially fling myself out of the car altogether. I didn’t dare breathe until we were safely approaching the East Bay Street exit.

To clutch the door handle was to potentially fling myself out of the car altogether. I didn’t dare breathe until we were safely approaching the East Bay Street exit. “Just don’t look,” he said. “Close your eyes and it won’t be a problem!” It sounded like a good idea at the time, but this is even worse than eyes open. Much worse! I squeezed my eyes shut, sat back and relaxed for what I know was a small eternity. I carefully opened my eyes only to discover that we had moved forward perhaps 20 feet. That meant we still had about two-and-a half miles to go before I could breathe again.

“Just don’t look,” he said. “Close your eyes and it won’t be a problem!” It sounded like a good idea at the time, but this is even worse than eyes open. Much worse! I squeezed my eyes shut, sat back and relaxed for what I know was a small eternity. I carefully opened my eyes only to discover that we had moved forward perhaps 20 feet. That meant we still had about two-and-a half miles to go before I could breathe again.